Central Refugee Camp Westerbork

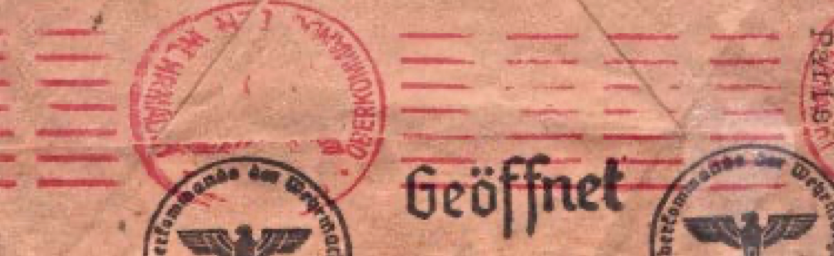

Incoming Mail – Foreign

Richard Zons was born in Cologne on November 23, 1901 and his wife, Dorothea Zons in Berlin on December 11, 1908. They had a daughter, Helga Renate Zons, who was born in Camp Westerbork on April 26, 1941. Mother and daughter were murdered in Auschwitz on October 6, 1944 while Richard died in “Central Europe” on February 2, 1945.

%20%E2%80%93%20Camp%20Westerbork%2C%20March%201%2C%201942.png)

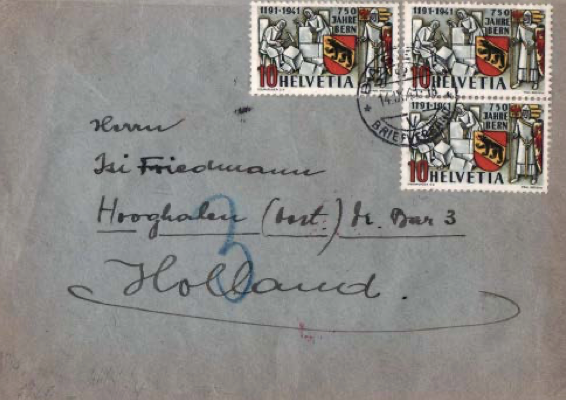

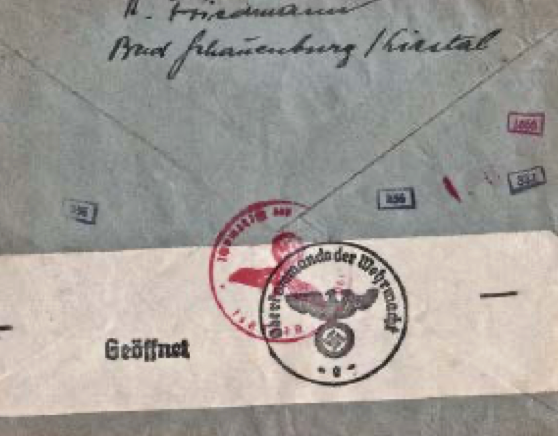

Isador (Isi) Friedmann was born in Bobrika, Poland on July 15, 1911. A bank officer, Friedmann came to Amsterdam from Vienna in 1938. He stayed in Camp Norg, Hellevoetsluis and Hoek van Holland. He was registered at Camp Westerbork on March 20, 1940. In the camp’s Jewish Council registry, he is referred to as “Alte Lagerinsassen” (old camp inmate). On February 15, 1944, he was deported to Bergen Belsen. He was subsequently sent on the “The Lost Train” to Theresienstadt before the train was liberated by the Red Army on April 23, 1945, in the village of Tröbitz. Friedmann apparently survived the ordeal, but later died in Tröbitz on May 9. 1945.

Correspondence with foreign countries was only permitted to pro-Nazi states and neutral countries such as Switzerland.

Outgoing Mail – Domestic

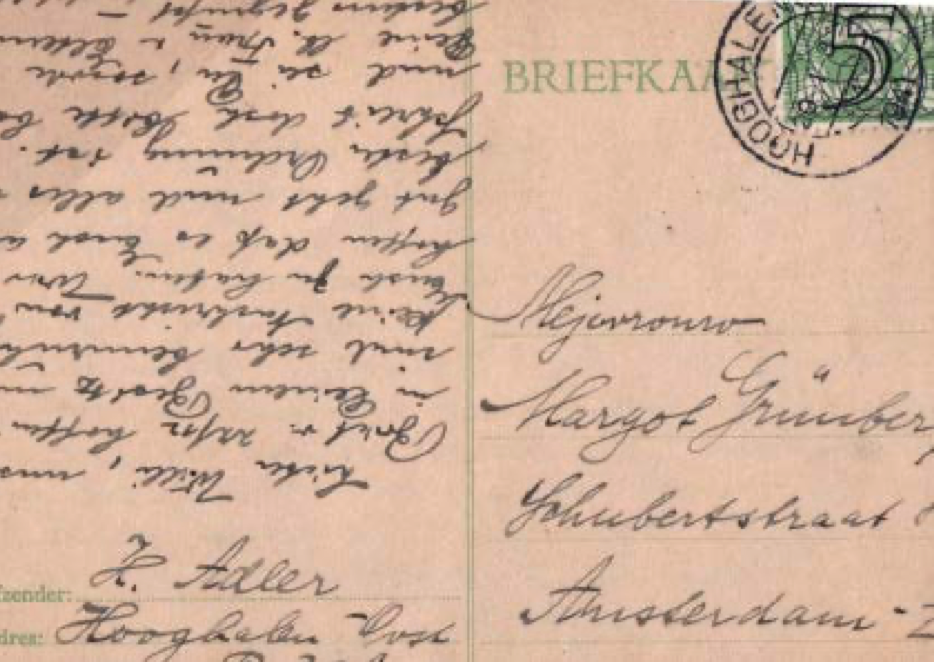

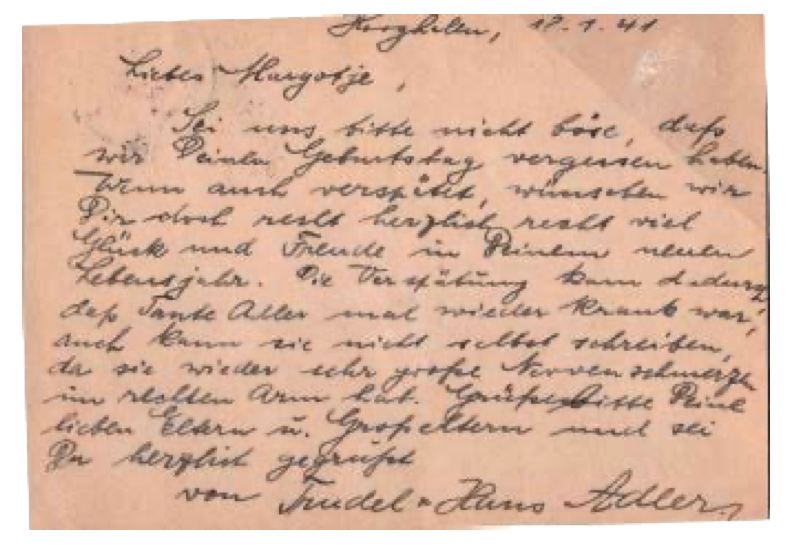

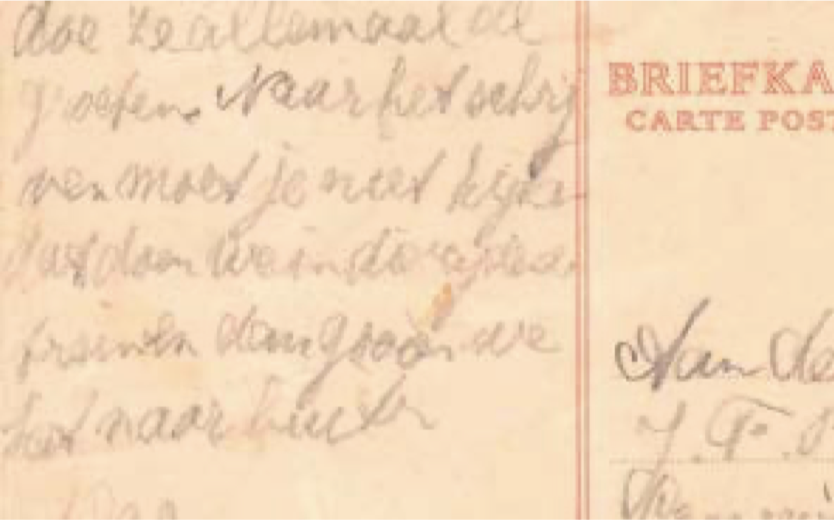

Postcard with Hooghalen cancel dated January 29, 1941, i.e. less than 3 weeks before Camp Order # 992 was issued. The letter was sent by Hans Adler in Camp Westerbork, Barracks 39A to Margot Grünberg, a student at the 1e Montessori Lyceum in Amsterdam. Adler was born in Lüdinghausen, Germany on August 1, 1915. He died in Auschwitz on September 30, 1942. Margot Grünberg was born in Berlin on January 10, 1929. She died in the Sobibòr Extermination Camp on April 16, 1943.

“…we hope that you received our letter of December 22 and we are extremely worried not to have heard any news from you…”

Outgoing Mail – Foreign

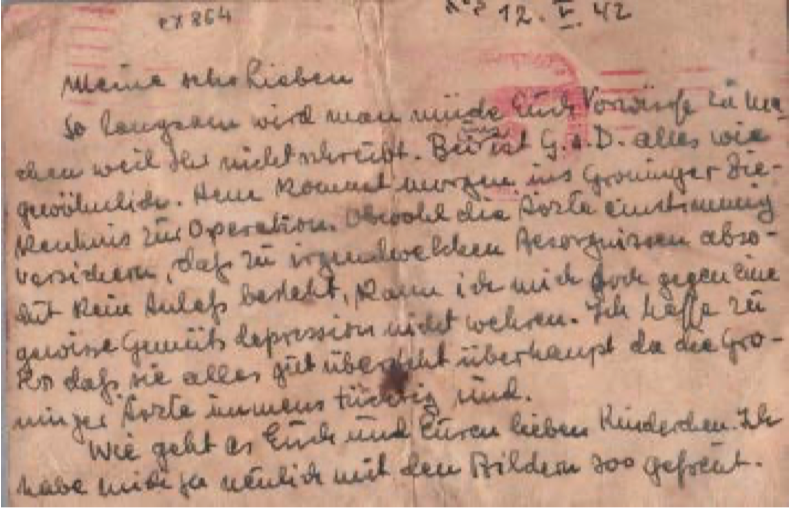

The card dated May 17, 1942, was sent by Hennie Birnbaum-Szaja. After leaving Berlin in 1938, she was interned in Westerbork in 1939, where she took care of orphans in the camp. She survived the war.

%2C%20May%2017%2C%201942.png)

The card was addressed to Konrad Bodzanowski, who, with his wife Helen, used to own a ladies apparel store in Berlin. They had a daughter, Hana, who donated the extensive family archive to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC after the war (Hana Wieder Collection 1926 –1956). In Hennie Birnbaum’s card to Konrad in Brussels she asks, “How are you two and your dear children doing?” suggesting that Konrad and Helena had at least two children. Further investigation has not shown what happened to the Bodzanowski family (but it is known that Konrad received a letter in Israel in 1956 advising him of the circumstances of his mother Regina’s death.)

Civil Internment Camps

The Indies Hostages

After the Dutch surrender to the Germans in May 1940, the Dutch East Indies remained free and unoccupied. German citizens living in the colony were arrested and interned to the outrage of German authorities.

In retaliation, 400 Dutchmen were arrested in Holland. They became known as the Indische Gijzelaars, the Indies Hostages. The Germans hoped that by arresting people who were on leave from the colony or had close ties with it, they would ensure proper treatment of the German internees. For this reason, the Indies Hostages were relatively well treated. Unlike the majority of civilian prisoners, they were allowed to receive Red Cross parcels, clothes and blankets. The Dutch hostages were initially taken to Zivilkonzentrationslager Buchenwald, but in November 1941, they were moved to Haarendael Major Seminary in the town of Haaren. They were then moved to Beekvliet Minor Seminary in St. Michielsgestel and then to a boarding school for boys called De Ruwenberg before finally being sent to Camp Vught. Camp Haaren became the generic name for the three Dutch locations where the hostages were held.

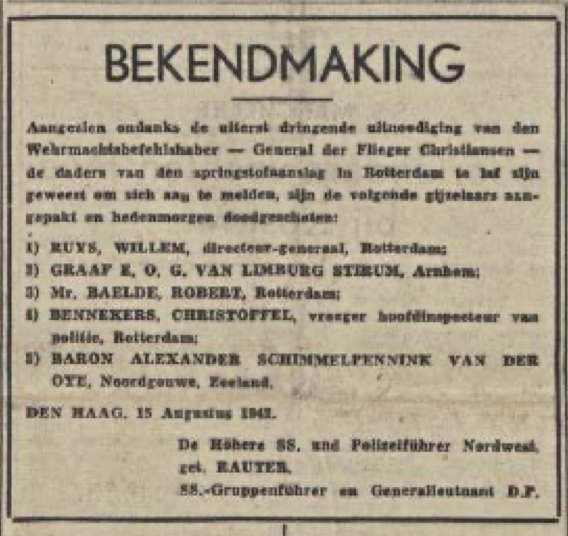

In 1942, another group of hostages, civilian internees, were interned at Beekvliet. They were well-known scientists, politicians, government officials and artists. The Germans expected to use these additional hostages to deter the Dutch underground from acts of resistance. Thus, these internees were referred to as “anti-resistance hostages:” However, when the resistance nevertheless carried out an attack on a Nazi troop train outside Rotterdam, the Germans executed five of these hostages on August 15, 1942.

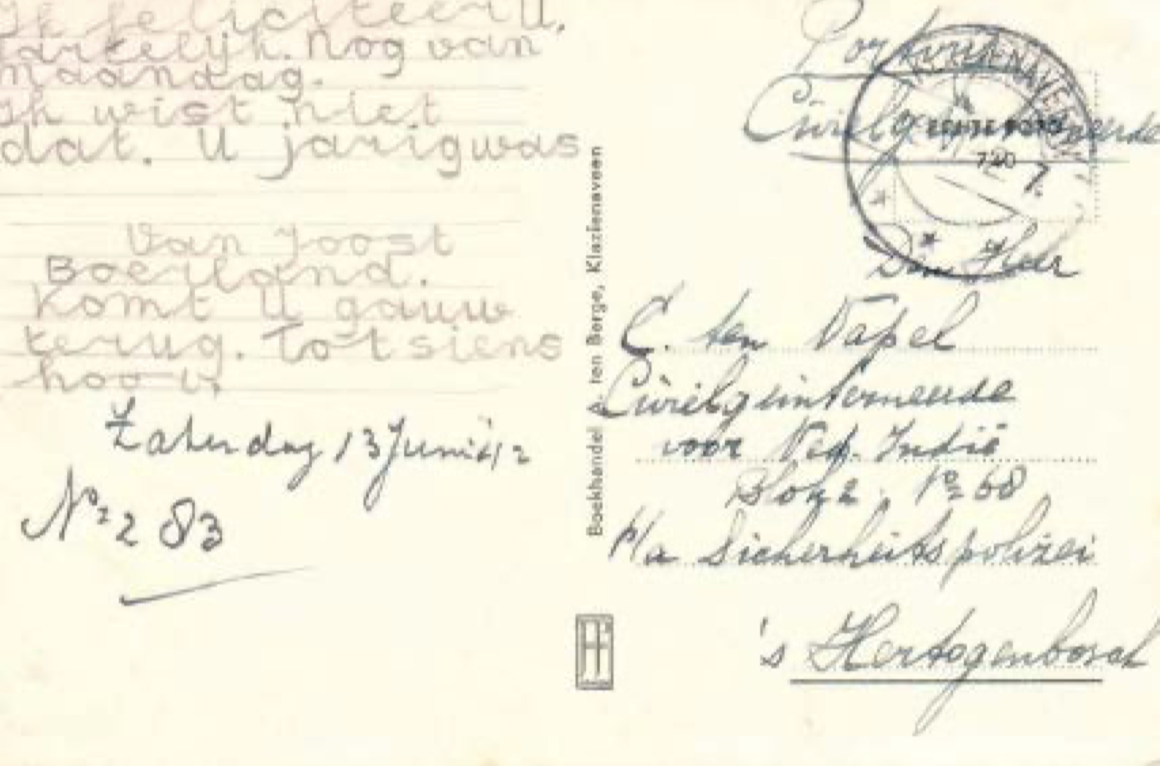

Incoming and outgoing camp mail was free of postage but had to pass through the SD, the Security Police in nearby s’Hertogenbosch. Internees were allowed to send one letter per week.

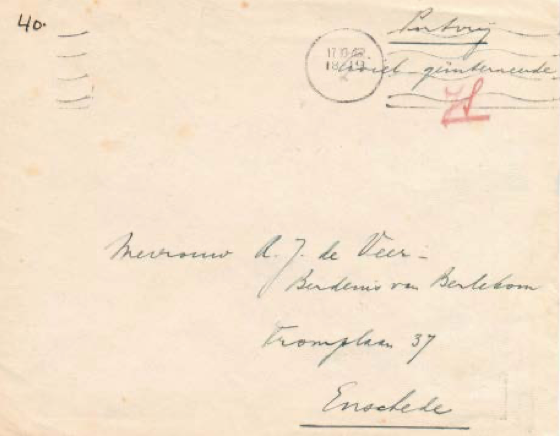

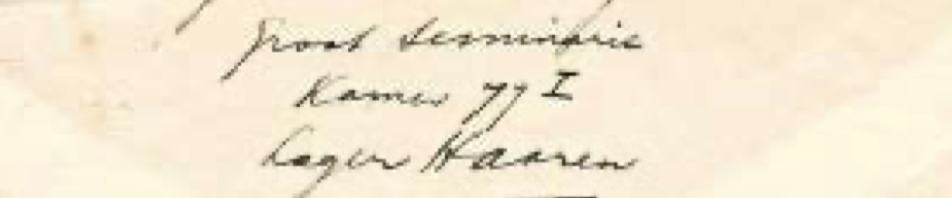

A letter sent from G.W.A. de Veer, born on April 22, 1904, in Amsterdam, a civilian internee in Room # 771 at the Major Seminary Camp Haaren to his wife, Mrs. R.J. de Veer. The censor’s initials were added in red. Mr. G.W.A. de Veer was a well-known philatelist and author who specialized in Dutch Railroad stamps. He survived the war.

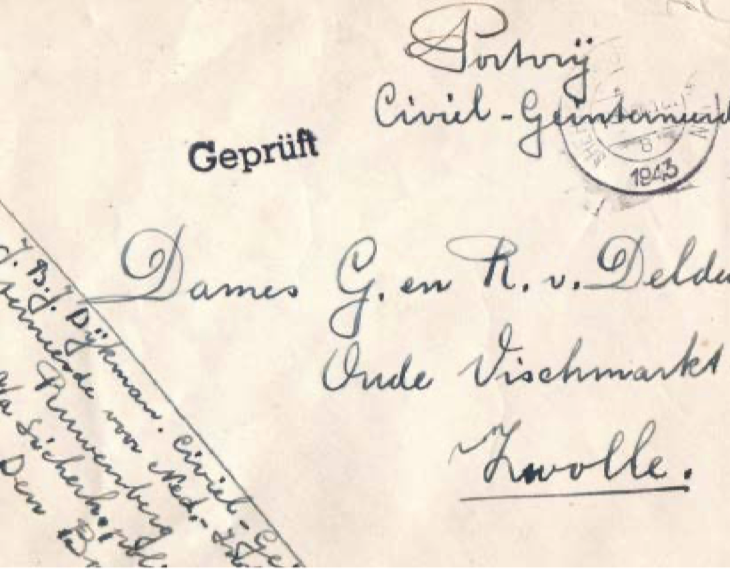

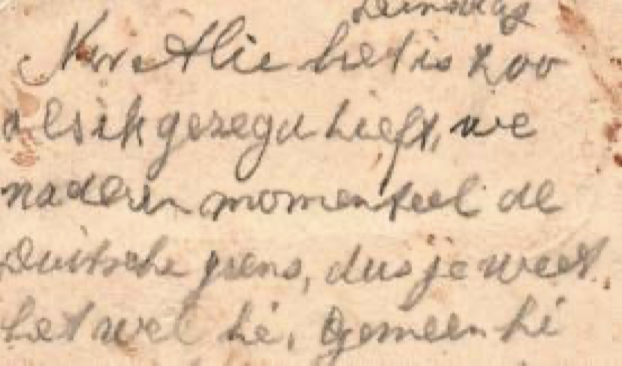

Letter to Dr. Tom Kruijff, a civilian internee in Camp Beekvliet from his wife in Utrecht. Dr. Kruijff, born on July 7, 1895, was employed by the Utrecht Province. His name appears in the UK National Archives as a Dutch helper of Allied airmen and other military personnel.

%2C%20August%2030%2C%201942.png)

Indies hostage J. Ph van Dalsum. was the principal of the Middelburg RHBS (high school). He was interned on May 4, 1942 and released April 20, 1944.

%20%E2%80%93%20Zeist%2C%20November%2025%2C%201942.png)

A postcard from an internee at Camp Haaren (De Ruwenberg) who listed his status as “Internee for the Neth Indies”.

%20%E2%80%93%20Geldrop%2C%20May%2010%2C%201943.png)

The sender, J.B.J. Dijkman (b. 1898), a high school teacher, was initially interned in Buchenwald. He was later transferred to St. Michiels-gestel, first in Haaren and then in Ruwenberg. He was eventually liberated at Camp Vught on September 17, 1944.

The Dutch Resistance

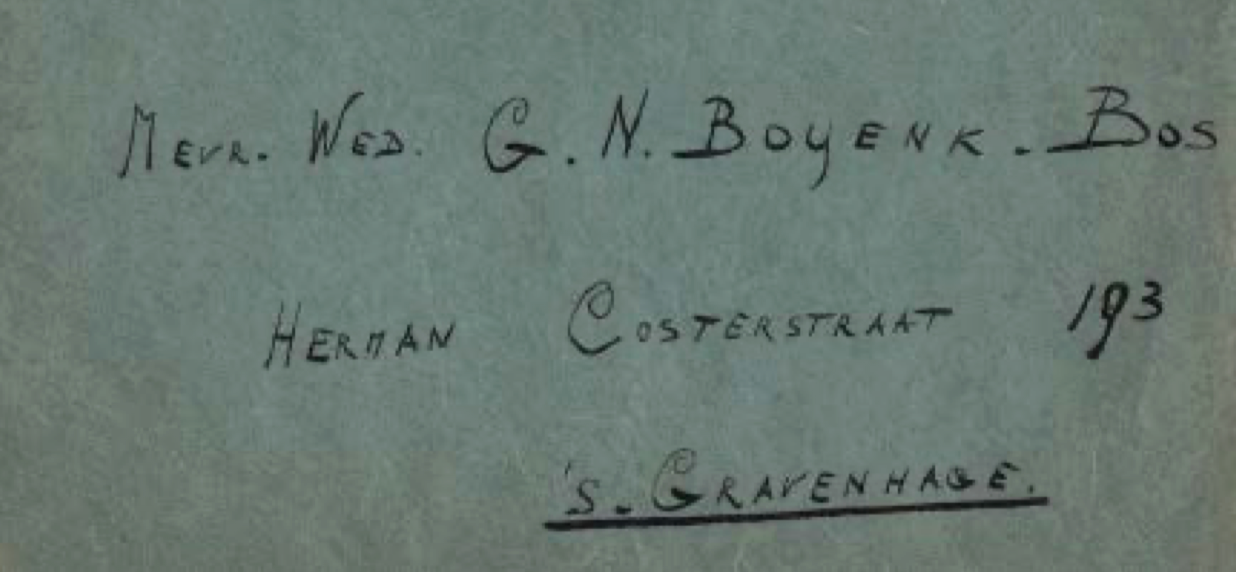

Archival records show that Pieter Dirk Boyenk born in The Hague on April 26, 1918, was a resistance fighter. This undated letter was written to his mother, Maria Elisabeth Boyenk-Bos, born July 28, 1883, married to Giles Nicolaas Boyenk, born August 5, 1878. Pieter was arrested by the Germans and detained in Cell # 346 at the infamous Hotel Orange.

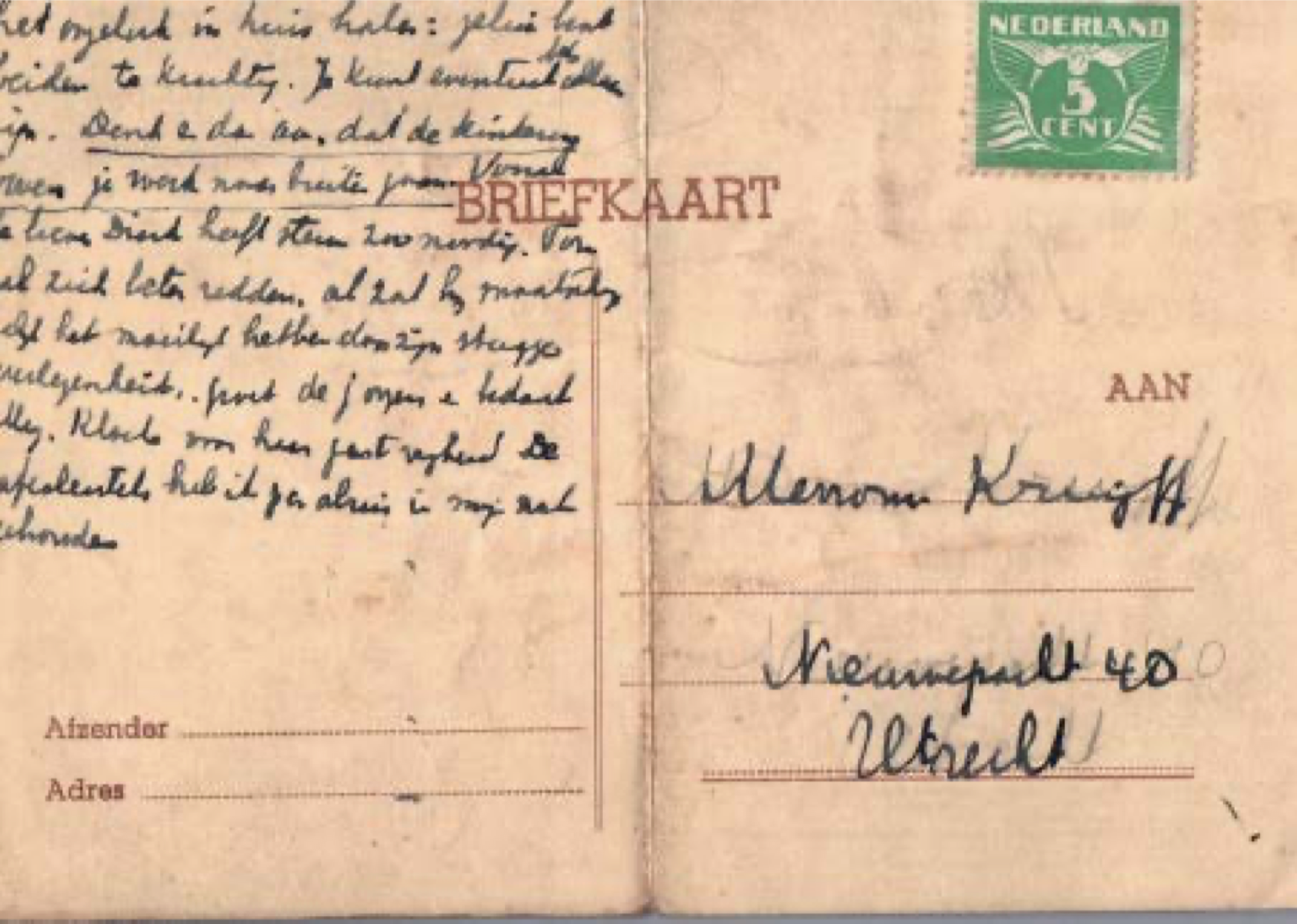

Franciscus J. Brehm, b. December 23, 1918, was a resistance fighter arrested in Rotterdam and detained in the local prison on May 5, 1944. He was subsequently transferred to Camp Amersfoort, and it is known that Brehm was moved to Zwolle on September 26, 1944. The card was mailed in Borne, some 50 km southeast of Zwolle, on Wednesday, November 15, 1944, and because it is dated “Tuesday” on the card, he probably started writing it the day before. Brehm addressed the card to his family in Rotterdam.

Well Alie, it is as I said. At the moment we are approaching the German border, so you know what is going on. Nasty isn’t it. But there is nothing that one can do about it. Let us hope for the best. I probably won’t be home now until after the war. If only we end up in one piece. Give my regards to everyone. Ignore the handwriting. We are writing in the freight train, and then we will throw it out.

While in the Fair Building (Utrecht) I was asked about my profession I had. My answer was insufficient for my release… The German Major said: I have made a decidision and that is “labor”. We left at 11:30AM and arrived in the infamous Camp Amersfoort at 5:00AM. Although I know that you will try everything possible, I don’t think that you will get me released. I only hope that I survive... Say hi to the boys, and thank Mrs. Kloche for her kindness. I accidentally kept the keys to the safe in my pocket.

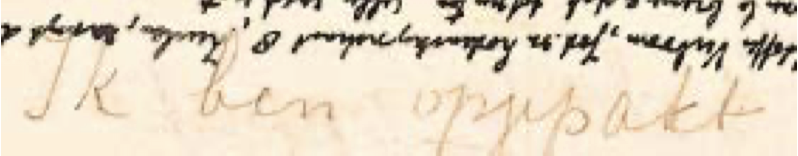

It is clear that the sender, T. Kruijff, had this card with him in case he was arrested. It was thrown from the train en route from Camp Amersfoort and picked up and delivered after being found alongside the tracks. The stamp is not canceled, and it was delivered outside the postal system. He also added in pencil “ik ben opgepakt”, "I have been arrested." Then he added one more note at the bottom: a co-victim asked that his wife be notified and that all is fine so far.