Transit Camp Westerbork (continued)

The Frederiks List - Protected by Privilege

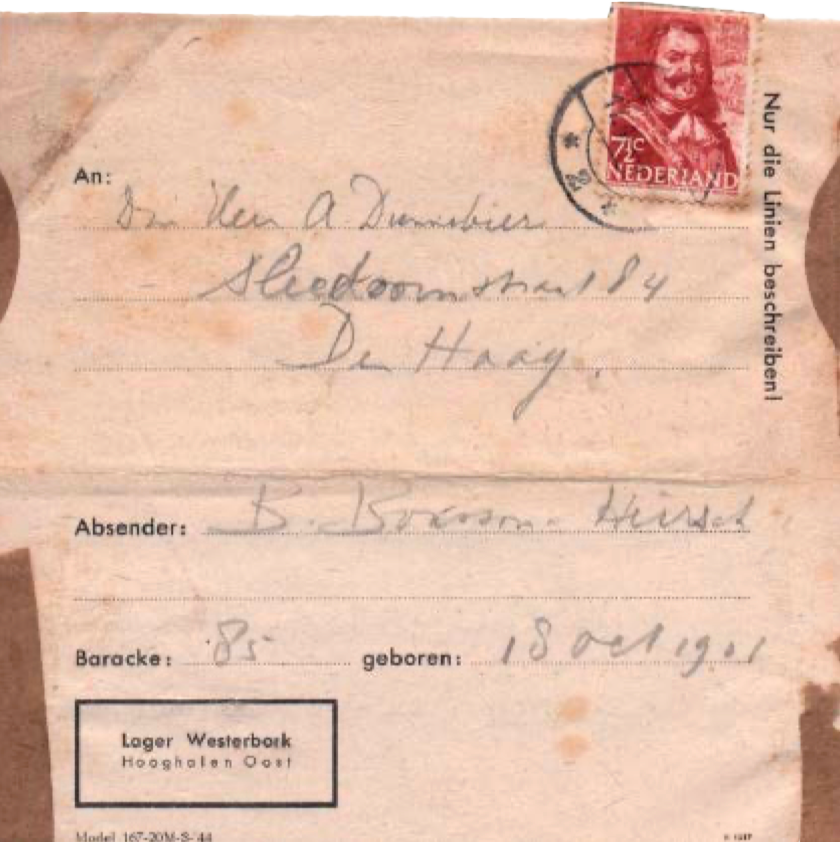

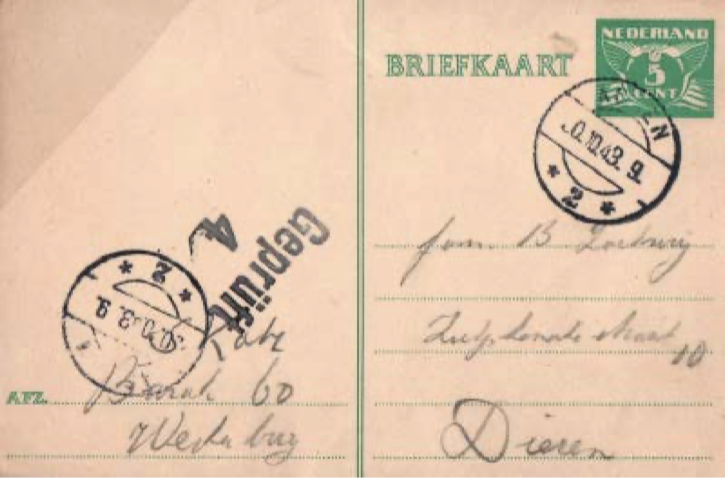

Form letter from Bernadine Boasson-Hirsch (also Heirsch) in Camp Westerbork to a friend in The Hague. Bernadine was interned at Barneveld on December 18, 1942. She arrived in Westerbork on September 25, 1943, and was deported to Theresienstadt on September 4, 1944. According to the registration card from the Jewish Council held in the Arolsen Archives, she had returned “to Eindhoven from Switzerland via Theresienstadt” and it also refers to her being on “Mr Frederiks - lijst I.” Her husband, a captain in the Dutch army, had died on the first day of the war.

The Frederiks Plan was conceived by Secretaries-General Frederiks and Van Dam who drew up a list of eminent Jews needing protection from deportation. It was created with the cooperation of the Germans after the Dutch government had fled to England. Jews on the list were placed in three villas in Barneveld and ostensibly protected from deportation. Although many were eventually transported to Theresienstadt via Westerbork, most survived the war.

This letter was sent by Mozes Speijer, a teacher. He and his wife were on the Frederiks List. Initially interned in the Schaffelaar Camp in Barneveld on February 27, 1943, they were transferred to Westerbork on September 29, 1943 and on September 4, 1944 to Theresienstadt where they were ultimately liberated.

Their son, Emanuel Speijer (b. 1904), was also on the Frederiks List. He was a biologist and a teacher like his father. While in Barneveld he started collecting bees, wasps and ants assisted by two professors from the Museum of Natural History who provided him with materials to set up the collection.

After his transfer to Westerbork, Emanuel worked for the “Hygiene Service” because of his knowledge of insects. He checked fought infestations of flies, lice, etc. in the barracks. He continued his activities in Theresienstadt where he dealt with outbreaks and prevented typhus by drawing up strict hygiene rules.

After the war his extensive collection was preserved in the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden. He died in The Hague in 1998 at age 95.

A Rembrandt for 25 Lives

%20and%20Benjamin%20(Ben)%20Katz.png)

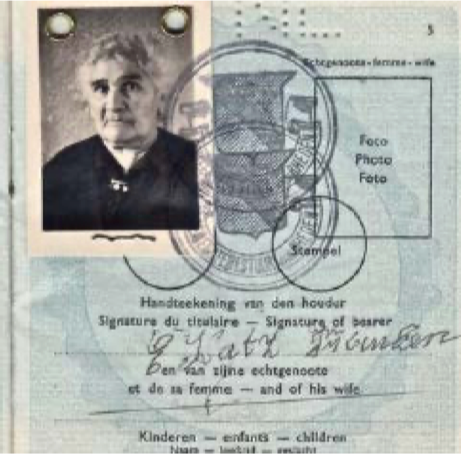

Eva Katz-Franken, born in 1869, lived in Dieren, as did her sons, the renowned art dealers Nathan (Nico) and Benjamin (Ben) Katz. Their firm, F.D. Katz, specialized in Dutch masters and had works by Vermeer, Ruysdael and Rembrandt in its inventory. The Dutch royal family was among their clients.

The Katz firm was well known to the Nazis because many of its pre-war clients had been German. Hitler’s agent, Dr. Hans Posse, acquired art for the Führer Museum planned in Linz, Austria. In October 1941 the Katz brothers and Posse agreed to exchange a desired Rembrandt painting for a letter of safe-conduct for 25 Dutch Jews. A darkened train with 25 Katz family members left Amsterdam, changed trains in Paris, and at the Spanish border their Stars of David were removed. When Ben Katz in Basel received confirmation that the family was safely in Spain, the painting was handed over to Dr. Wiederkehr, the notorious dealer of human lives. The Katz family members eventually boarded a ship to the Caribbean where they would stay and return to Holland after the war.

As part of their deal for the Rembrandt, Ben and Nico Katz also arranged for their mother not to be sent to a camp. She died at home on November 9, 1944, at age 84.

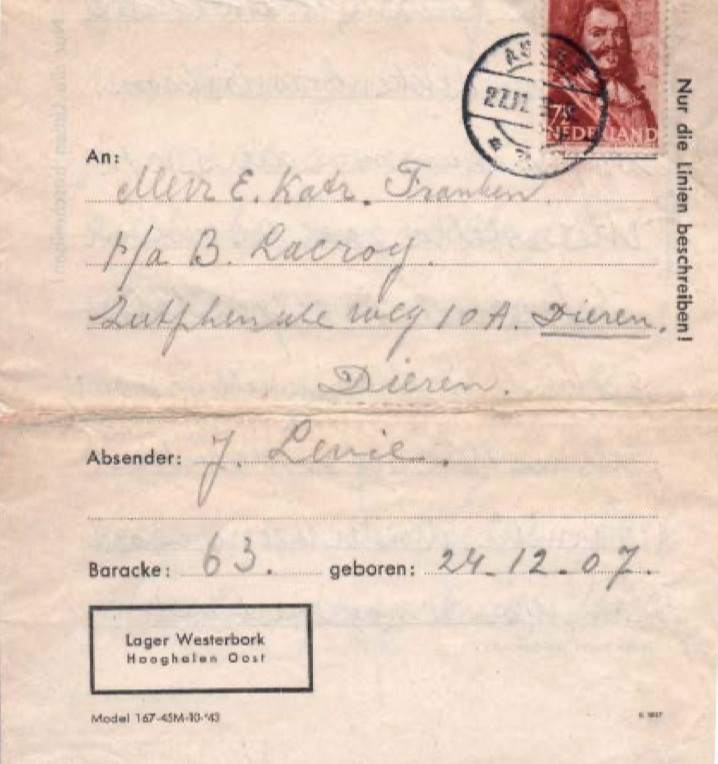

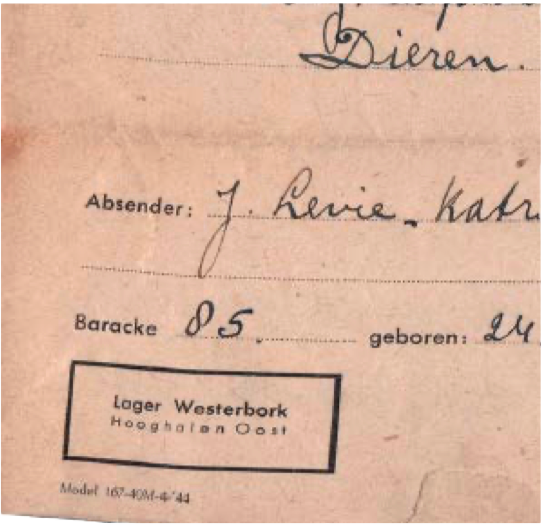

Concern for her mother might also have been the reason Sibella Levie-Katz and her husband Joop Levie had decided to stay behind, as well as the guarantee from the Nazis that four other members of the Katz family who stayed behind would not be touched. It turned out to be an empty promise and they were sent to Camp Westerbork

Sibella is ill and in bed… We have to move to barracks 63… Do you hear from Nico or the rest of the family?

The Rembrandt painting, “Portrait of Dirck Jansz. Pesser,” was returned to Ben Katz and now hangs in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. (CC BY-NC-SA Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

From Sibella Levie-Katz to her sister, Mina, and son, Ben: “…send letters here or postcards with stamps because I am without money and cannot pay for postage … send me 2.50 guilders per month.”

Sibella Levie-Katz

%20stamps.png)

Sibella’s last letter, sent from Camp Westerbork to her mother, is dated August 31, 1944. Less than two weeks later, possibly on the very last train that left the camp on September 13, she was deported to Concentration Camp BergenBelsen on November 18, 1944.

As the end of the war approached, the SS instructed concentration camps to destroy records and either murder the remaining prisoners or transfer them elsewhere before Allied troops arrived.

The train with 2,500 Jewish “passengers” that left on April 10, 1945, is known as “The Lost Train,” since Allied bombings prevented it from going to Theresienstadt. It crisscrossed Eastern Germany aimlessly for two weeks unless it ended up at Tröbitz, near Leipzig, on April 22. The train crew had already run when Red Army soldiers finally opened the train doors and liberated the prisoners.

For almost 600 of them, the liberation came too late; they had died on the train. Among them was Sibella Levie-Katz, age 56. She was buried in Schipkau, 4 meters from the railroad tracks on the edge of the forest.

Sibella Levie-Katz

Herman Wallega, a Dutch Jew, lived with his family in Leeuwarden. At 3.15 pm on an early June day in 1942, Herman bought a bag of apples in Terpstra’s Fruit Hall. Jews were not permitted to shop past 3 pm, and Herman was betrayed by a Dutch member of the pro-German NSB. He was promptly arrested and shortly afterward sent to Westerbork and then to Auschwitz, where he was murdered on August 13, 1942, at 40 years old.

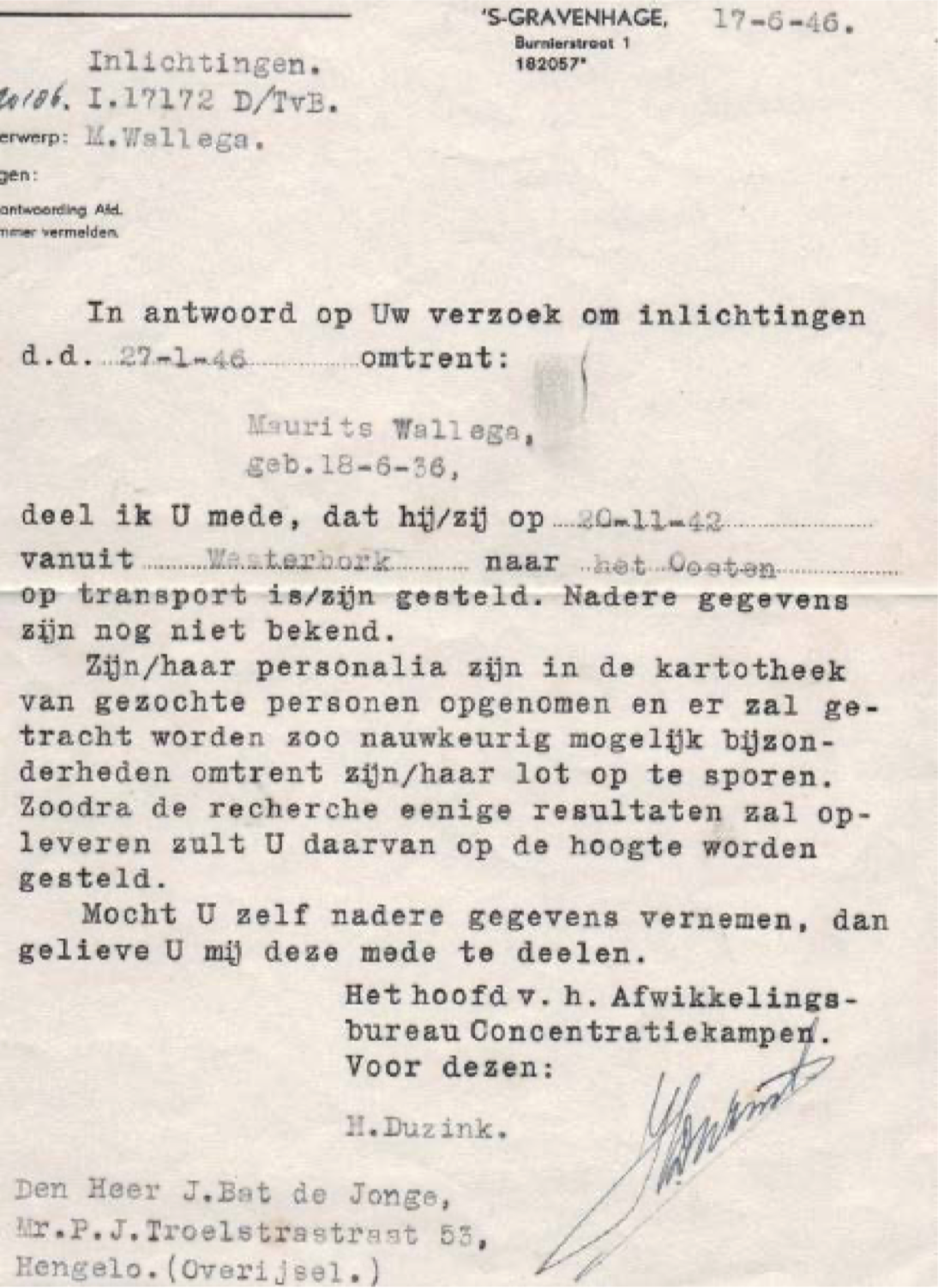

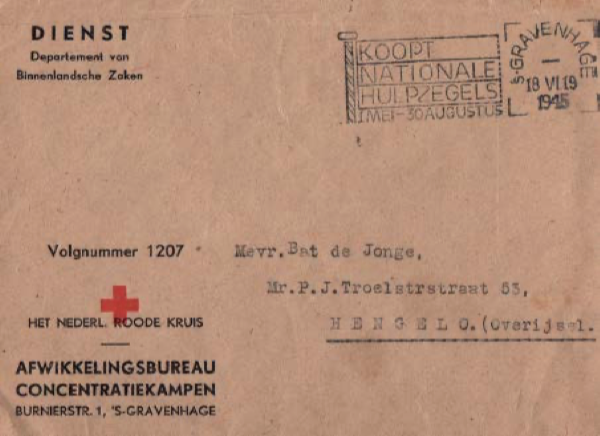

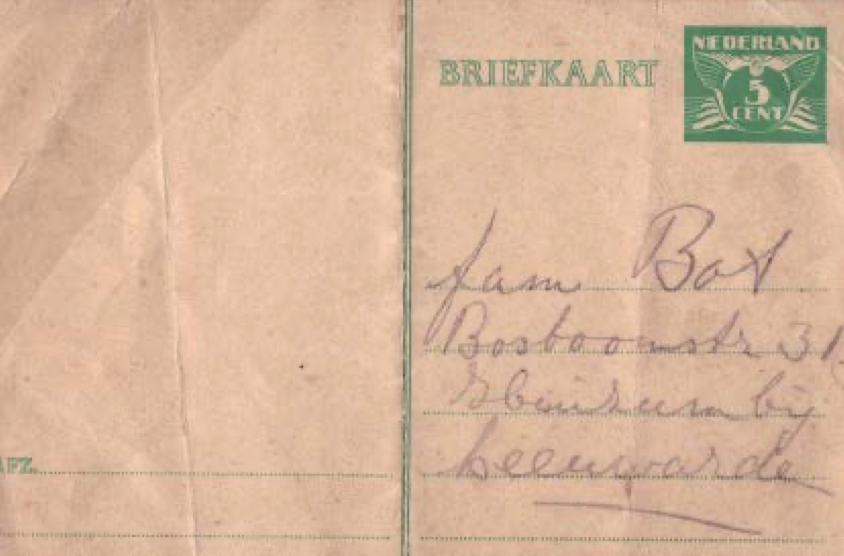

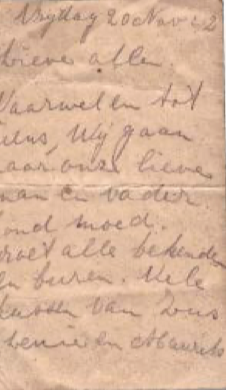

Shortly afterward, his wife Marianne (36) and their children, Helena (12) and Maurits (6) were taken to Westerbork, unaware of what had happened to Herman. On Friday, November 20, 1942, they too were en route to Auschwitz. Marianne threw this postcard to her neighbors, the bat family, from the train. It would be picked up and eventually delivered. Marianne, Helena and Maurits Wallega were murdered in Auschwitz on November 23, 1942, three months after Herman. After the liberation in May 1945. Mrs. Bat de Jonge, who was the recipient of Marianne’s postcard, enquired about the fate of her friends. There is extensive correspondence with the Red Cross Afwikkelingsbureau Concentratiekampen, the department ‘finalizing’ matters related to concentration camps.

The first envelope addressed to her is dated June 18 , 1945, indicating that Mrs. Bat approached the Red Cross as soon as the war ended. She was initially told that “because of the overwhelming number of enquiries, it is impossible, to provide information in the near future.”

Farewell and until we meet again. We are going to our husband and father. Keep up your courage. Greet all friends and neighbors. Many kisses from Zus (Marianne’s nickname), Lenie and Maurits.

Then she received four letters, all dated June 17, 1946, one for each of the Wallega family members. It confirmed that all ‘had been put on transport to the east from Westerbork’ and that ‘further information is not yet known.’ By this time, the Bats fully understood what was meant by being sent “to the East”. The Red Cross confirmed their worst fears.